What's good about offset pagination; designing parallel cursor-based web APIs

I was recently writing a little program to back up the data I’ve put into various social platforms over the years 1. While doing Goodreads, I was reminded that its API is a bit of an oddity because it uses offsets for pagination 2, something that’s understood to be bad practice by today’s standards. Although convenient to use, offsets are difficult to keep performant in the backend, and have the major undesirable property that any items which are inserted or removed shift the entire result set over across all subsequent pages. Goodreads’ API has been around for a long time, and presumably it uses offsets by virtue of that fact alone, as many of its contemporary APIs did.

Initially, my program did what it was supposed to do, and naively iterated pages one by one. It fetched page one, then two, then three, and kept going until finding one with an empty set of results. This worked fine, but one of the Goodreads API’s other quirks is that it is slow. API calls took so long that my program took 35 seconds to iterate just a few hundred objects.

Luckily, offset pagination does have one very distinct advantage – dead easy parallelizability. Cursor-based pagination is difficult for a client to parallelize because it can’t know what cursor to send for the next page until it’s received the previous one. The API will send back a list of results along with a cursor that specifies where to go next, like “here’s some results, now get the next page at /objects?starting_after=tok_123”. Not so with offset pagination, where I can not only ask for page 1, but pages 2, 3, and 4 all at the same time.

I refactored my program to use a simple divide and conquer strategy. Choose a number of consumers, break the page space into equal parts, and have each consumer advance along the pages in its chunk:

const numSegments = 6

var mutex sync.RWMutex

var readings []*Reading

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(numSegments)

for i := 1; i <= numSegments; i++ {

segmentNum := i

go func() {

page := segmentNum

for {

pageReadings, err :=

fetchGoodreadsPage(&conf, client, page)

if err != nil {

...

}

if len(apiReviews) < 1 {

break

}

mutex.Lock()

readings = append(readings, pageReadings...)

mutex.Unlock()

page += numSegments

}

wg.Done()

}()

}

wg.Wait()

The reduction in runtime was textbook perfect. With six consumers, the program went from 35 seconds to run down to 6. Wow, offset pagination sure is great. Everyone should use it.

Designing parallelizable cursor-based APIs

But Goodreads is a bit of an aberration here. If all modern APIs use cursor pagination, then offset parallelization doesn’t help us does it?

Well, although cursor-based pagination doesn’t parallelize quite as easily as offset, it’s still possible using a similar principle.

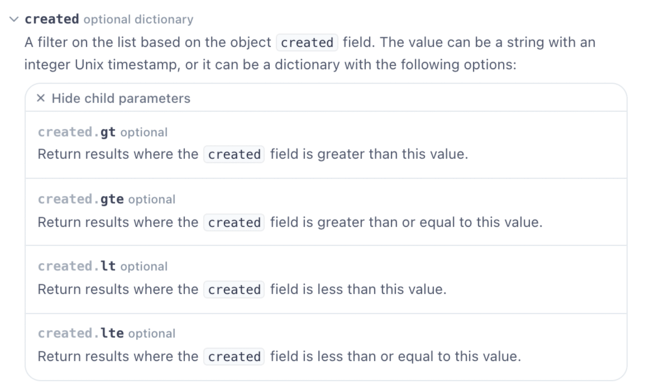

The key is to allow at least one other filter to be specified that would allow users to break up the total search space into parallelizable parts. For example, Stripe’s API allows many list endpoints to filter based on when a resource was created:

Each list endpoint is entirely cursor-based, but clients can divide and conquer by breaking up the total timeline they’re interested in into N parts for N consumers, then have each one make list requests with upper and lower time constraints. Each consumer gets a separate cursor, and they paginate happily along their own segment with no duplication.

This is still efficient to implement on the backend because even with the additional filter, it’s easy to make sure the list can still use an index. Just like with a filter-less cursor, none of the additional offset-related accounting is needed. It’s fast for the client and fast for the server.

It’s worth noting though that using something like a created timestamp works for this purpose, but it’s not perfectly optimal because it requires consumers to discover the upper and lower time bounds for themselves, and would be challenging to parallelize when objects aren’t distributed uniformly across the timeline. Say you had 100 objects created in 2018, 1,000 in 2019, and a million in 2020. You couldn’t break 2018-2020 into equal chunks and expect the work to parallelize well.

A really friendly API provider could probably introduce something like a counter specific to each user and object type that increments roughly in line with new objects being created, and allow users to filter on that. Clients could then check the maximum bound, do some simple division based on number of consumers, and go to work.

1 Exporting data from Goodreads has become more important of late as they’re planning to retire API access completely.

2 More specifically, it’s actually page based (?page=1), but on the backend is the functionally the same as being offset-based.