Slack, and the case for bar-raising (instead of lowering)

A few weeks ago Slack replaced the input text box which previously exclusively allowed formatting to be done in Markdown with a WYSIWYG 1 version.

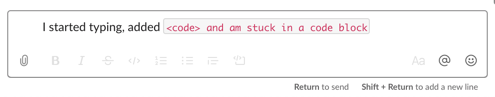

The change may have been benign had it been backward compatible, but that wasn’t the case — along with the new tiny buttons were a number of regressions that compromised the original Markdown features. Users would find themselves unable to close a code element they’d started, or unable to create two formatting blocks side by side.

Rarely has there been such a vehement backlash from the Hacker community over a change, with an angry thread skimming a 3,000 point horizon as I publish this. And it seems to have worked – Slack has indicated that they’ll add a toggle to return to a Markdown editor, a concession they’d previously refused to even consider.

Efficiency on the altar

Beyond the bugs and reduced usability, there’s the more profound argument that when it comes to the basic text formatting elements in use 99% of the time — bold, italic, code, lists, etc., WYSIWYG is fundamentally slower. Markdown is more efficient in that it requires fewer clicks and keystrokes, so a fast Markdown user will outpace a fast WYSIWYG without fail, every time.

The thought process of Slack’s product people leading to the new editor is pretty clear. In their minds, Markdown may have been an acceptable convention for the early hackers who seeded the platform, and it may have some technical advantages, but is far too complex for a dull-witted majority.

And to be fair, this brand of thinking isn’t unique to Slack. Many of us have argued for years that the transition from desktop to mobile OSes like Mac OS to iOS are highly similar in that they trade power and productivity for an aesthetic veneer and rock bottom barrier to entry.

Rising tides

It doesn’t have to be this way. Instead of lowering expectations to the lowest common denominator, the lowest common denominator can be ratcheted up. People are smart, and even though learning curves for some techniques are non-zero, with a bit of education and practice, they can get there.

To see an example of a major success in this area we need look no further than the keyboards and QWERTY layout that most of us are using right now (be it on computer or phone). QWERTY seen for the first time would have seemed cruel and unusual, with letters arranged arbitrarily so that the position of each one had to be discovered individually. The original typewriters would have seemed to necessitate an unlikely leap in public competence to ever see wide operation.

But we did it — a huge portion of the world can type in one form or another, and to great effect. You can make the argument that modern speech input is finally reaching comparable input speed, but for decades typing has been a faster way to get words down on paper/screen compared by full multiples. The same simpletons who couldn’t possibly learn Markdown are happily clacking away right now on QWERTY from that new WYSIWYG editor.

Instead of lowering the bar by forcing the world to WYSIWYG, we can raise it by teaching. Markdown is a great place to start.

1 WYSIWYG means “What You See Is What You Get”, a long-time computing term describing an editor that shows you a fully formatted result as you edit.