Speed and Stability: Why Go is a Great Fit for Lambda

A few days ago in a move foreshadowed by a hint at Amazons’ re:Invent conference late last year, AWS released support for Go on its Lambda platform.

Go users can now build programs with typed structs

representing Lambda event sources and common responses in

the aws-lambda-go SDK. These can then be compiled,

bundled up into a “Lambda deployment package”

(as simple as a ZIP file with a binary in it), and added to

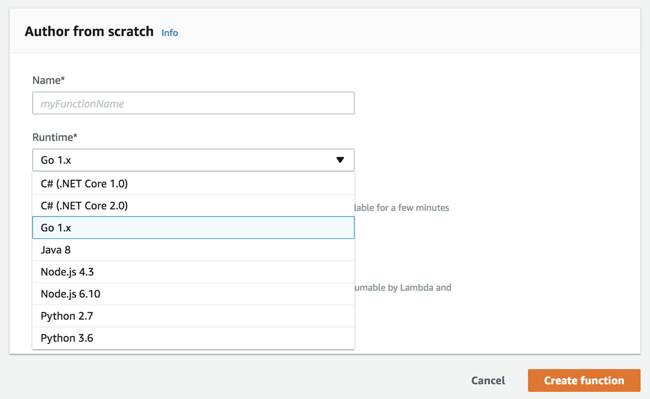

a new Lambda function by selecting “Go 1.x” as a runtime.

Go fans around the world are undoubtedly celebrating the addition, but Gopher or not, this is a big step forward for everyone. Go may have its share of problems, but it has a few properties that make it an absolutely ideal fit for a serverless environment like Lambda.

Lambda runtimes are special snowflakes

Lambda’s exact implementation details have always been a little mysterious, but we know a few things about them. User processes are started in sandboxed containers, and containers that have finished their execution may be kept around to service a future invocation of the same Lambda function (but might not be). Between function invocations containers are frozen, and no user code is allowed to execute.

Containers also flavored with one of the preconfigured runtimes allowed by Amazon (this list is current as of January 16th):

- Node.js – v4.3.2 and 6.10.3

- Java – Java 8

- Python – Python 3.6 and 2.7

- .NET Core – .NET Core 1.0.1 and .NET Core 2.0

- Go – Go 1.x

That’s a pretty good variety of languages, but more

interesting is what’s missing from the list. While .NET

Core and Python are relatively up-to-date, Java 9 is

absent, along with any recent major version of Node (7.x,

8.x, or 9.x). Notably, major features like async/await

(which landed in Node ~7.6) are still not available on

the Lambda platform even a year after release.

These holes tell us something else about Lambda: new runtimes are non-trivial to create, run, and/or maintain, so updated versions often lag far behind their public availability. Given that Lambda will be four years old this year, it doesn’t seem likely that Amazon will be able to to address this deficiency anytime soon.

The remarkable tenacity of 1.x

That brings us back to Go. Lambda’s Go runtime specifies version “1.x”. At first glance that might not look all that different from other languages on the list, but there’s a considerable difference: Go 1 was first released almost six years ago in March 2012!

Since then, Go has followed up with nine more releases on

the 1.x line (and with a tenth expected soon), each of

which carried significant improvements and features. And

while it’s rare to ever have a perfect release that

doesn’t break anything, Go’s done as good of a job as is

practically possible. Generally new releases are as pain

and worry-free as changing one number in a .travis.yml.

This level and length of API stability for a programming language is all but unheard of, and it’s made even more impressive given that Go is one of the most actively developed projects in the world – a far shot from being stable only because it’s stagnant. The only way this remarkable feat has been made possible is that (presumably) having experienced the pain involved in the API changes that come along with most language upgrades, Go’s team has made stability a core philosophical value.

There’s an entire article dedicated to the policies around stability for the 1.x line. Here’s an excerpt where they explicitly call out that programs written for 1.x should stay working for all future versions of 1.x:

It is intended that programs written to the Go 1 specification will continue to compile and run correctly, unchanged, over the lifetime of that specification. At some indefinite point, a Go 2 specification may arise, but until that time, Go programs that work today should continue to work even as future “point” releases of Go 1 arise (Go 1.1, Go 1.2, etc.).

The APIs may grow, acquiring new packages and features, but not in a way that breaks existing Go 1 code.

This might sound like normal semantic versioning (semver), but semver only dictates what to do in the event of a breaking change. It doesn’t say anything about frequency of change, or committing to not making breaking changes. Go’s proven track record in this area puts it well ahead of just about any other project.

That brings us back to Lambda. If we look back at our list of runtimes, the supported versions across languages might not look all that different, but it’s a reasonably safe bet that the “Go 1.x” in that list is going to outlive every other option, probably by a wide margin.

Static binaries, dependencies, and forward compatibility

The Lambda guide for Go suggests creating a function by building a statically-linked binary (the standard for Go), zipping it up, and uploading the whole package to AWS:

$ GOOS=linux go build -o main

$ zip deployment.zip main

$ aws lambda create-function ...

This is in sharp contrast to other support languages where you send either source-level code (Node, Python), or compiled bytecode (.NET Core, Java). Static binaries have some major advantages over both of these approaches.

Static linking removes the need for a dependency deployment

system, which is often a heavy part of other language

stacks. Anything that’s needed by a final program is linked

in at compile time, and once a program needs to execute, it

doesn’t need to think about project layout, include paths,

or requirements files. Source-level dependency management

has been a long criticized blindspot of Go, but with the

addition of the vendor/ directory in Go 1.6 and rapid

uptake on the new dep dependency management tool,

the future is looking brighter than ever.

Static binaries also carry the promise of forward

compatibility. Unlike even a bytecode interpreter, when a

new version of Go is released, the Lambda runtime may not

necessarily need an update given that existing containers

will be able to run the new binary. Time will tell for

sure, but unlike Node users who are still transpiling to

get async/await on Lambda, Go users should be able to

push updated programs on the release day of a new version

of Go 1.

Stability as a feature

It’s rare to write software and not have it come back to haunt you in a few year’s time as it needs to be fixed and upgraded. In a craft generally akin to the shifting sands in a whirling windstorm, Go is a rare oasis of stability. More recently there has been some speculation as to what Go 2.0 might look like, there are still no concrete plans for any major breaking changes, and that’s a feature.

Along with the languages normal strengths – incredible runtime speed, an amazing concurrency story, a great batteries-included standard library, and the fastest edit-compile-debug loop in the business – Go’s stability and ease of deployment is going to make it a tremendous addition to the Lambda platform. I’d even go so far as to say that you might want to consider not writing another serverless function in anything else.

1 This comes with the caveat that net/rpc package that

aws-lambda-go uses for the entrypoint

remains stable across versions. This is reasonably likely

though given that the package has been frozen for

more than a year, and net/rpc’s serialization format,

encoding/gob, states explicitly that efforts will

be made to keep it forward compatible.