T plus four weeks into isolation. It’s been an experience. I’ve been one of the lucky ones so far, getting away mostly with some vitamin D deficiency and minor eye strain caused from going from staring at e-screens just the normal amount of too much, to staring at them around-the-clock-and-then-some. I hope yours hasn’t been catastrophic.

As usual, this is Nanoglyph, an experimental newsletter about software and gaming-in-place. If that’s not your thing, warp whistle back the real world with a one-click unsubscribe. (And if you’re reading from the web, you can subscribe here).

A side effect of my brave new commute-free bar-free travel-free existence is over the last couple weeks I’ve found myself with more free time than ever before in my adult life. Some of that windfall’s been used well (daily runs, morning and evening calisthenics, excavated guitar from the layer of dust that’s been accumulating since roughly the Paleozoic), some of it not-so-well (binged multiple TV series not worth the hours of human life it took to watch them), and some of it in the middle. You might reasonably ask, what’s a “middle” activity? There’s one in particular I had in mind: video games.

The last decade’s seen gaming enter the mainstream after spending a long time cast in common wisdom as the favored hobby of social misfits and basement dwellers, but despite some progress on the PR front, it’s still a long shot from being considered a virtuous pursuit. Some of that’s history, and some of it’s from the continued existence of its darker elements: multiplayer games like MMOs eat every waking moment of an enthusiastic player’s existence to the detriment of all else, micro transactions are the ancient act of profiteering honed to razor sharpness with 21st century technology, and loot boxes seem to be designed to show kids how to be out-of-control dopamine-driven gamblers.

But enjoyed the right way, video games are some of the most transportive media produced by humanity today. Photorealistic graphics take players to vibrant alien worlds of impossible vistas and unspeakable wonder. Stories are richer and more expansive than their counterparts in film or TV because there’s more time and opportunity to explore. Writing and acting in top games might fall a little short of the very best that Hollywood has to offer, but if so … not by much. A notch above the last season of Game of Thrones anyway.

I’m as much of a fan of a great TV series or movie as the next person, but often come away from that sort of passive consumption experiences feeling like a vegetable. Best case scenario, I viewed something complicated and cerebral with rapt attention throughout. More often, I’m watching at about half attention, with the other half on a second screen like a laptop or smartphone (and I’m not alone). But a video game is different. There’s no choice except to be 100% engaged, and often in a way that’s stimulating the mind. And I’m not just talking about Myst – even outside of puzzle games, you’re optimizing an equipment load out, understanding a skill system, or deciphering the attack patterns of a final boss.

Over the years, I’ve adopted a certain discipline for time spent on games to maximize enjoyment and minimize waste. I only play the handful of top rated games for any given year – that means less time burned on bad ones, and even a few games are good for 100s of hours of entertainment. I don’t play multiplayer – the gameplay dynamics required to create a working online ecosystem make grinding (playing long hours to build skill or generate in-game resources) an inherent property, and the trade off’s not worth it for me. I’m a casual gamer through and through – thrown into a DOOM deathmatch, I’d be put to peaceful rest by your run-of-the-mill six year old. I’ve come to okay with that.

With that out of the way, here’s a couple recommendations from the last couple years. Skip ahead a few sections for more technical content.

A most wholesome dystopia

Horizon Zero Dawn (also pictured at the top) is easily one my favorite games of all time. You play as Aloy, a young huntress brought up as an outsider in a tribe of hunter-gatherers in a distant post-apocalyptic future. The greater world is a dangerous place as it’s overrun by robot dinosaurs, and as wacky as that sounds – it works.

The combat is some of the best ever developed for a console 1. It centers around a bow and arrow, and the mechanics of such – a slight delay in drawing, aiming for (destructible) weak spots on your dino foes combined with a subtle bullet time effect strike a perfect compromise between challenge, satisfaction, and fun.

The writing, voice acting, and graphics are all top notch. Careful design was even applied to the UI so that little tasks like healing or crafting ammunition aren’t slow or annoying. Moving around the world is so much fun that I found myself completing every side quest with no prompting.

As Aloy makes her way through the world, puzzle pieces slot into place, and a plausible story for the game’s ludicrous premise starts to emerge. If you make it that far, the end of the story is sublime, heartfelt, and beautiful.

Dad of war

I held off playing the PS4 headliner God of War) for a long time because I assumed it wasn’t my thing. A guy with an axe with a little kid following him around the whole time? I’m getting annoyed just by thinking about it. Well, after judging this book by its cover for a long time, I finally played it and boy was I wrong.

Previous entries in the God of War franchise are set squarely in a world constructed on Greek mythology, but this one takes a hard left turn by placing Kratos in the realm of Midgard 2, surrounded by Norse gods and figures of lore instead of their Greek counterparts. The story purposely leaves a gaping hole in the plot between itself and previous entries, opening with Kratos and his new son who the player’s never met, coming to terms with the recent death of his mother and Kratos’ lover, who the player has also never met. They set out on a journey to fulfill her last wish – that her ashes be spread at the highest peak of the nine realms.

Like Horizon Zero Dawn, combat focuses on many successive fights of relatively few challenging enemies. It starts with the basics of light and heavy attacks, parry, and dodge, but takes on limitless depth with the addition of new skills throughout. Kratos’ primary weapon is the Leviathan Axe, which (in a nod to Thor’s hammer Mjölnir) has the power to return to his hand after he throws it. The solid feeling of the axe’s heavy blows, transferred to the player through a combination of spectacular visuals and force feedback through the controller, is one of the most masterfully designed weapon experiences, ever.

(Warning: Continued use of superlatives to follow.)

The game’s world is gorgeous – upon discovering a new region, I often found myself fumbling for the controller’s “Share” button to take a screen capture the same way I would fumble for my camera in real life. The post-game material, including the grinding needed to get the very best armor, is shockingly fun to the point where you barely notice you’re even doing it. The voice acting is superb – Christopher Judge (Teal’c from Stargate) as Kratos is possibly the most perfect actor/character fit in recorded audio, and listening to Mímir 3 tell old norse myths as you paddle around the world is filler that’s better than 95% of TV/movie/radio hours ever produced. Its technical excellence is impressive – really, the graphics are legitimately breathtaking, and there are no loading screens throughout (although some tricks are employed to delay the player until new areas are ready).

Great video games don’t just stand up well to other video games, they stand up well to any other form of media including our greatest film and literature. At the risk of sounding like an uncultured pleb, as someone spending part of their quarantine slogging through James Joyce’s Ulysses, I wouldn’t mind giving you some strong opinions as to when compared to the masterworks above, which is the greater form of art.

Another World

Fabien Sanglard, author of the Game Engine Black Book series has written a great blog series starting with The Polygons of Another World. Although nominally about the 1991 game, it’s really more of a case study in the system design of a whole line of computers and consoles from Amiga to Jaguar. The first article starts with background, then each subsequent examines the architecture, quirks, and game implementation on every new system including architectural schematics, color palettes, and screenshots.

Another World makes a particularly compelling case study because over the years it’s been ported to so much hardware. Fabien’s series covers seven systems from the 80s and 90s, and since then it hasn’t even stopped, with 2020 releases on PS4, Xbox One, and Switch. Its 2D polygons were well-suited to graphical gymnastics that let it run on surprisingly underpowered hardware – the game shipped in ‘91, but supported the Amiga A500 that predated it by almost five years with its original release in ‘87.

A few highlights:

- It was able to run on the Amiga A500 largely thanks to its “blitter” 4, a dedicated co-processor that performed data transfer in parallel with the CPU. The blitter could be used to quickly fill polygons and draw their borders with a specialized “draw line mode”, acting like a primordial ancestor to a modern GPU.

- The Atari ST eventually featured a bitter as well, but too late in its lifecycle for many games to make use of it. Another World renders entirely in software on the ST’s Motorola 68k processor. This is only made possible thanks to its graphical style of wide single-color cells – most of the frame could be drawn quickly in 16 pixel blocks, with finer edges drawn with slower per-pixel operations (see the screenshot below – the red sections needed precision drawing, but everything else is a block).

- A challenge of porting to the IBM PC was the variety of hardware that might be under the hood. The game had to ship with two sets of color palettes – one to support the modest 6-bit TGA/EGA color standards, and another for the 18-bit VGA.

- The SNES was designed to accommodate developers with extraordinary requirements and to that end reserved part of its bus address space to support a custom chip inside the cartridge itself. (How cool is that?) Another World bundled a modest one to keep per-unit costs down (SlowROM), but by storing a scanline of polygon data there, was able to boost performance 10% and hit target framerates.

- For the Game Boy Advance, which sported an ARM7 chip, the entirety of the original game’s incompatible 68k assembly was ported back to C, then re-optimized.

- With so much extra available power on the Atari Jaguar, its Another World port runs through a specialized JIT compiler that optimizes the game to make use of the system’s graphics hardware. It makes use of remastered 1152x720 256-color backgrounds, making the game’s look a far shot from the original.

Staring at the screenshots of Another World reminded me of is how far games have come just in my lifetime. We’ve gone from games consisting of nothing but jagged lines and primitive shapes which depended on the player’s imagination for 99% of their effect, to fully realized 3D worlds with graphics more reminiscent of reality than not, lifelike characters, and detailed interactive narratives that put the linear storylines of even our greatest works of fiction to shame.

Imagine what happens in the next 30 years.

Cell chips and tempest engines

Speaking of, we’ve recently been indulged with details on the next generation of console hardware. The PS5’s specs were supposed to be revealed in a developer-facing talk at GDC this year, but after it was postponed for the virus, Sony streamed a virtual alternative instead.

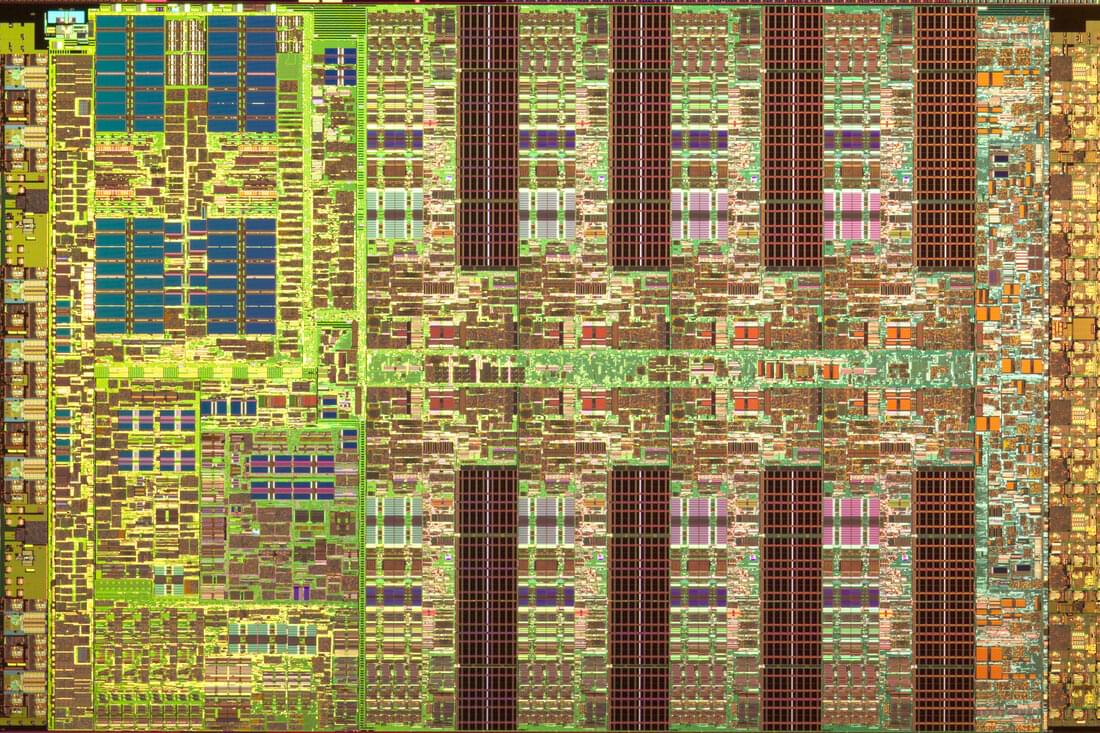

Next gen gaming console hardware is itself a game, in marketing. This might most infamously embodied by the PS3’s Cell architecture, which before release was hailed as so groundbreaking that it would change the state of the art forever. It featured only one powerful primary core (a “PPE”, or power processor element), but an incredible eight secondary cores (SPEs, or “synergistic” processing elements). The dream was that games would be massively parallelized, with one core doing the heavy lifting, secondary functions farmed out to SPEs, and the parts assembled to become a unified experience firing on every cylinder. Unfortunately, developers found it difficult and time consuming to make that work in practice, especially compared to the Xbox 360’s simpler model of three hulking, symmetrical 3.2 GHz cores. Games that came along later in the PS3’s lifecycle like The Last of Us were finally able to make good use of Cell, but it overpromised and underdelivered for years, especially for multi-platform titles where publishers needed to target more than one system.

The cell processor’s die. The four boxes in the upper left are its 512 kB L2 cache. The PPE is the section just below that on the lower left. The eight symmetrical bars to the right (occupying most of the chip!) are the SPEs.

But I give Sony’s marketing people a pass on the embellishment because it just feels so good to be excited about hardware again. Computation in the PC market has become enough of a commodity that we’re more interested in form factor and battery life than anything else. Consoles are one of the last places where hardware is being built to push the envelope in performance because the coming generation of titles is fully expected to make use of it.

The PS5 won’t have anything quite so exotic as Cell. Both it and the Xbox Series X will make use of AMD’s Zen 2 architecture – the same one used in Ryzen and Threadripper PC chips which by all accounts are eating Intel’s lunch. The PS5 will run 8x Zen 2 cores at 3.5 GHz.

PC gamers will be amused to know that the biggest performance gains compared to the last generation are expected to stem from the fact that PS5 will have an SSD, making Sony late to the game by only a decade or so. To be fair, it’ll be a monster of an SSD, with off-the-charts performance at 5.5 GB/s and 8-9 GB/s in practice as hardware-level decompression is used to move then decode data stored as zlib or the even more performant Kraken. Given how impressive the loading times were on the PS4 and its spinning disks, the PS5 should be extraordinary (based on Sony’s numbers, the increase in I/O throughput from the hard disk compared to the PS4 is on the order of 100x).

The PS5’s most quixotic feature is its “Tempest Engine”, a dedicated compute unit designed to usher in a new era of audio fidelity. The example they used was that while rainfall in games today is a uniform prerecorded sound, the Tempest Engine will bring that rain to life by modeling the unique character of every individual droplet as it lands on a surface and echoes back to a player’s ear. True innovation or another Cell? We’ll know soon enough.

Bullet time

This article does a great job of describing the implementation of bullets in 3D games. Nothing hugely surprising, but an aspect that’s not necessarily obvious is that games will use different techniques depending on the effect they’re trying to achieve and the weapons they’re modeling.

Simple, fast guns as seen in something like Call of Duty might use a “hitscan” to figure out where a bullet should go based on a player’s location and the direction they’re facing; equivalent to firing off a beam of light that instantly makes its way to its target. A more complex weapon like a rocket launcher will treat projectiles as full 3D entities with their own mass, velocity, and hitbox.

On a less technical front, this is a wonderful character piece on Hideo Kojima from the NYT.

I’ve never been a huge fan of his games, even if I respect his work. When I was in high school I went to a friend’s house so that he could show me the epic hour-long plus cinematic sequence at the end of Metal Gear Solid 2. I made it ten minutes before literally falling asleep. Reviews of Death Stranding read like reference letters written by hostages for their captors after being trapped in a Stockholm bank with them for a week (“not many of what you’d call traditional values, slightly misguided, but has a lot of heart”).

But I love the cult of personality surrounding Kojima. It’s powerful, and hard to explain.

Kojima proceeded to play perhaps the strangest three and a half minutes of video ever to grace the E3 stage. Keep in mind that this is a venue where cybernetic dinosaurs and giant-felling samurai are par for the course. The video opened with a William Blake poem, the first lines of “Auguries of Innocence,” then cut to a close-up of highly realistic computer-generated sand. The camera floated over the sand, revealing a jumble of dead crabs. Handprints appeared in the sand and then filled up, inexplicably, with black goop. The handprints led to a naked man lying on the beach, his left wrist locked in glowing handcuffs. A black cord connected the man to what appeared to be a tiny infant, lying next to him on the sand. The man rose to his hands and knees and crawled over to the baby and picked it up and cradled it in his hands, bringing it to his chest, and his face was revealed and it was … Norman Reedus from “The Walking Dead”? And he was weeping hysterically?

There was no hint as to the story, the gameplay or even the genre of the game. It was all mood and symbol and Norman Reedus’s shiny posterior. It was more like something you’d see at MoMA than at E3. But the crowd went wild.

In the first Metal Gear Solid, Psycho Mantis breaks the fourth wall to demonstrate his psychokinetic powers by physically moving your controller (the built-in rumble pack might have some hand in it too). Metal Gear Solid 3 features a sequence where you do nothing but climb a ladder for an excruciating two real-world minutes. Death Stranding is a Fedex simulator with the skeleton of a social network bolted on. If there’s one person out there who’s pushed the envelope on creativity to the point where it’s resting against a backdrop of sheer weird, it’s this guy, and it’s hard not to admire that.

There’s something deeply engrained in the nature of the human condition that predisposes us to having heroes. It’s natural, even healthy – it’s good to have something to aspire to. You could do worse than Kojima.

Congratulations, you’ve unlocked the Voracious Conqueror of Newsletters achievement by making it this far. Thanks for reading. As usual, feel free to hit reply and tell me what I’m not talking about.

1 Shooting arrows in Horizon Zero Dawn is one of the best and most satisfying combat mechanics on any system, but is edged out ever so slightly by a truly great FPS played on PC with a mouse and keyboard. e.g. Half-life 2.

2 Midgard is the name for Earth in old Germanic cosmology. The realm inhabited by humanity as opposed to Asgard, inhabited by the gods, or Jotunheim, realm of giants.

3 Mímir, best known for his well of knowledge, to which Odin sacrificed his eye in pursuit of wisdom. Second best known for being a talking head who is carried and recounts secret knowledge to Odin after being separated from his body during the Æsir–Vanir War.

4 The name “blitter” comes from the “bit blit” operation of the Xerox Alto, which stands for bit-block transfer.