Last year, I rebooted a dormant sushi hobby, and bought an excessively elaborate kitchen knife to go with it – 52 layers of hammered Japanese steel and fashioned in the style of a Damascus blade. Highly functional for chopping things; all pleasing aesthetic lines.

It wasn’t a one-time transaction. It might be bought only once, but it needs maintenance forever. Always use a cutting board. Not being stainless steel, don’t leave it wet. Sharpen regularly. To help with that last point, I even bought an honest-to-goodness whetstone (a nice benefit of the commodity age, it was only $30 on Amazon) and learned to use it via the globe’s most preeminent tutor, YouTube. Submerge for 10 minutes to let it absorb water, sharpen on the coarse grit, flip the stone, sharpen on the fine one. A little laborious, but satisfying.

A single sharpening session yields some lasting benefit, but the real key is engage in them regularly. All work performed with the tool gets a little more fluid and a little more efficient. Intense, periodic investments for small, frequent yields over a long time.

I can’t remember where I was first introduced to the idea of tool sharpening in the context of software, but the analogy translates nicely from physical to virtual. A few times a year, take a break from writing code, and spend some time doing nothing but improving the environment that helps you write it. Like the metaphorical knife, the idea is to spend a little effort occasionally to tighten up your workflow in the 99% of the time.

It can apply to any tool in your belt: configuring Vim, discovering new VSCode plugins, learning a few more IntelliJ/Pry/GDB shortcuts, or even just remembering one new oft-used key binding on Mac OS. It’s useful to keep a list of the small day-to-day points of pain that you run into in your environment so you’ll have some obvious points to investigate when the time comes.

Here’s a few recent ones from mine:

- Create a single shortcut in Vim to yank the path of the current file.

- Get a VSCode plugin that will copy a GitHub link for the selected line(s) of code to clipboard or pop it open in a browser.

- Figure out why LSP in Ale/Vim only works ~70% of the time.

- Find an easy way to copy the current path of a Finder window.

- Get IntelliJ’s Vim plugin to share the system clipboard so that I can easily copy/paste in and out of the app.

This post was originally broadcast in email form. Can I interest you in seeing more like it? Nanoglyph is never sent more than once a week.

Enter Alfred

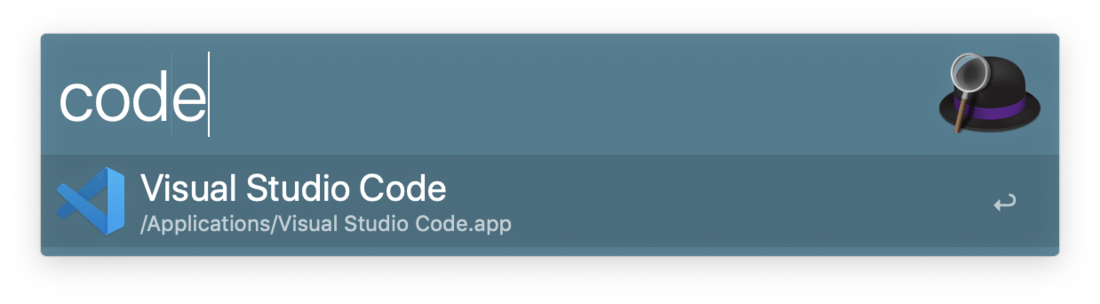

A tool that I sharpened recently is Alfred, an application launcher for Mac OS. It’s a particularly good one, but the idea isn’t novel – it was around years before Alfred in the form of applications like QuickSilver, and the functionality is even partially baked into Mac OS itself with Spotlight. Users on other operating systems won’t be using Alfred specifically, but will have access to a similar tool.

Its most prominent feature is being able to match items intelligently based on a substring. Although not quite fuzzy matching, it lets you type the first few letters of any application, see a match on screen in the most minute fraction of a second, and hit Enter to launch it. The whole process happens in the blink of an eye – an observer unfamiliar with the concept wouldn’t easily be able to say what happened.

Alfred distinguishes itself by being a simple program that’s highly refined, but also by being pluggable. Beyond looking up applications, it’ll find files, perform calculations, control a music player, and a host of other things. It already bundles pretty much everything anyone would ever need, but can be expanded with user-defined workflows for even more expressive customization.

Bookmark cultivation

I’ve never used bookmarks in web browsers a lot because since about the mid-2000s URL completion has been so good that it remembers just about anything I ever want to get to, and googling for anything it doesn’t is as fast as clicking up into a bookmarks menu and visually searching the list. Alfred gave me a reason to start using them.

Under the “Web Bookmarks” feature, you can have Alfred search your bookmarks along with applications or other configured items. It’s especially useful for work, where I bookmark dashboards, documentation, favorite Splunk queries, admin control panels, etc. It’s a reliable and very fast way of getting to anything you care about – beating the speed of a Google search, and definitely that of fiddling around with a mouse in a (possibly hierarchical) bookmark menu.

Single-step search

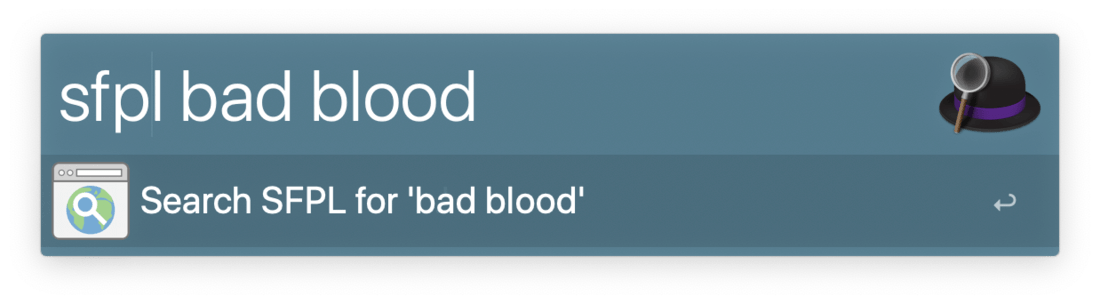

Under “Web Search”, Alfred supports custom search engines which are invoked by a configurable prefix and define a URL which a query is plugged into:

https://splunk.corp.example.com/en-US/app/search/search?q={query}

This works well for frequently used public servers, like a local library, but really shines for internal services like log aggregators, exception trackers, or corporate search. Here are a few of mine along with the prefixes they’re keyed to:

sp: Splunk (multiple actually, production andqspfor QA)st: Internal corporate searchsfpl: San Francisco public libraryamz: Amazon

Everyone’s custom search list is going to be different, but everyone does have a list. Considered in a singular sense none of these shortcuts saves you much – just a single page load and a few seconds at a time (instead of loading page, entering query, and getting results, you enter the query immediately, and get results). But considered in aggregate, it’s a lot. Each of my engines is used hundreds to thousands of times a year. Clocking in at a few seconds per use, that’s serious return.

Configure once, distribute everywhere

There’s nothing worse than spending a lot of time on configuration, then losing it every time you set up a new computer. Luckily, Alfred supports dumping its configuration to a .plist at a location of your choice – perfect for having it slurped up into Dropbox, then reclaimed when bootstrapping a new machine. Browser bookmarks are not saved, but both Chrome and Mozilla provide separate mechanisms to sync those between devices.

Licensing

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a software person that doesn’t buy a lot of software. Consciously, I’m all in on supporting developers and know it’s the right thing to do, but there’s a feeling deep in the back of my mind that if I opt into commercial software now, there’s a good chance it becomes a recurring cost, and lock in makes it hard to get out. Affordable now, but with a lifetime cost of ownership that’s uncomfortably high. Think of all those poor Oracle users out there.

I’ve been using the free version of Alfred for almost ten years, and bought a license for the first time a few months ago. The free version is so generous that it didn’t even buy me that much – the one paid feature I’m using is the teal theme – but I’ve gotten 100 licenses worth of value over it over that period, so the time was right. I bought the £45 edition that comes with lifetime upgrades.

Alfred’s major feature isn’t what it can do – every one of these things can be done from somewhere else – rather, it’s the speed at which it can do it. A well-optimized Alfred workflow is driven entirely by muscle memory and happens in the blink of an eye. It’s a perfect example of using computers for fast, learned productivity, which is what PCs should be all about.

Modular is beautiful

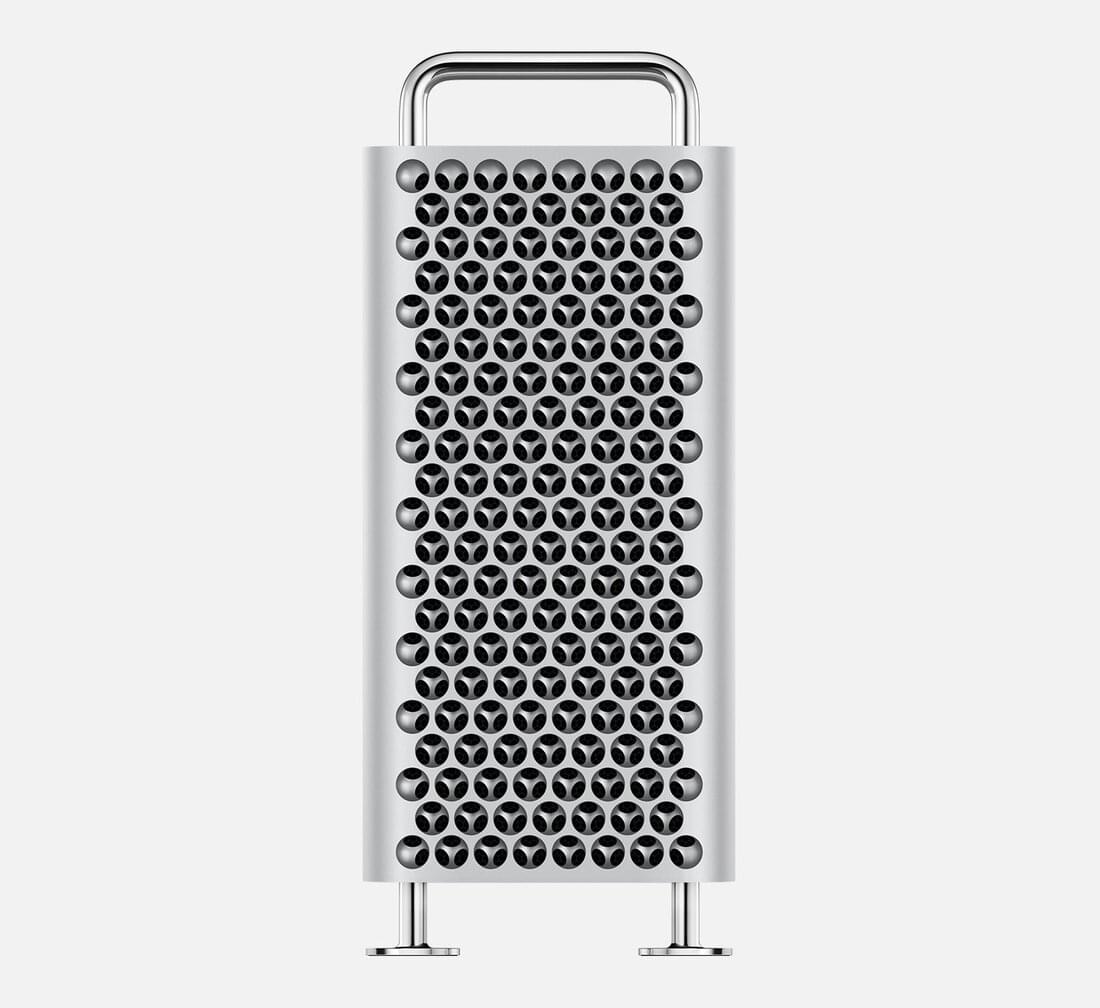

Speaking of tooling, iFixit’s teardown of the 2019 Mac Pro is a great read. Its case is removable in mere seconds, replacements and upgrades are possible without even a common screwdriver, and Apple’s even gone so far as to etch maintenance diagrams right into the computer itself which show, for example, how to distribute RAM across DIMM slots based on the capacity installed.

Their repairability rating of 9⁄10 for the Mac Pro isn’t just unusually high – it’s in a different dimension compare to anything else Apple makes. The latest generation of iPhone gets a previously-high-for-Apple 6⁄10, the 2019 MacBook Pro a dismal 1⁄10, and every model of AirPods ever made a perfect 0/10. That’s an encouraging turnaround which we can only hope might have a tiny influence on their other product lines – maybe on other product lines that don’t cost as much as a midrange car.

Until next week.