Scaling a High-traffic Rate Limiting Stack with Redis Cluster

Redis is the often unspoken workhorse of production. It’s not often used as a primary data store, but it has a sweet spot in storing and accessing ephemeral data whose loss can be tolerated – metrics, session state, caching – and it does so fast, providing not only optimal performance, but efficient algorithms on a useful set of built-in data structures. It’s one of the most common staples in the modern technology stack.

Stripe’s rate limiters are built on top of Redis, and until recently, they ran on a single very hot instance of Redis. The server had followers in place for failover, but at any given time, one node was handling every operation.

You have to admire a system where this is even possible. Various sources claim that Redis can handle a million operations a second on one node – we weren’t doing that many, but we were doing a lot. Every rate limiting check requires multiple Redis commands to run, and every API request passes through many rate limiters. One node was handling on the scale of tens to hundreds of thousands of operations per second 1.

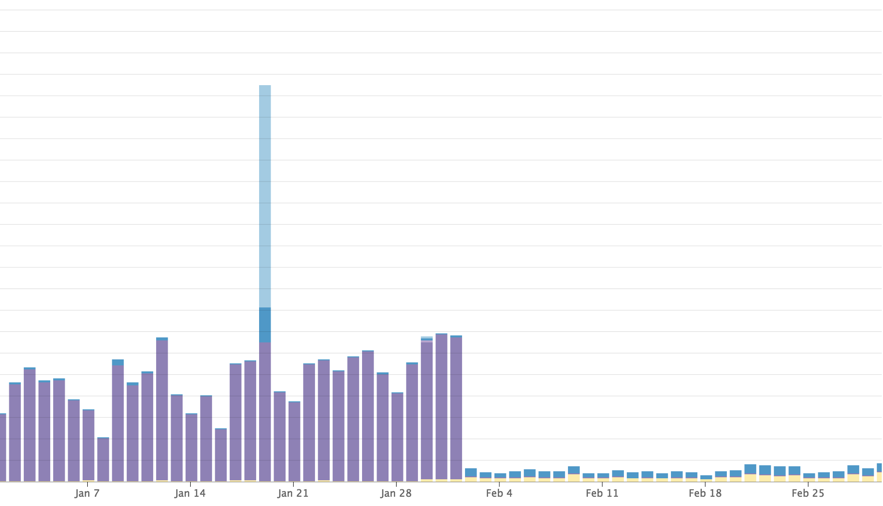

The node’s total saturation was leading to us seeing an ambient level of failures happening around the clock. Our services were written to tolerate Redis unavailability so most of the time this was okay, but the severity of the problem would escalate under certain conditions. We eventually solved it by migrating to a 10-node Redis Cluster. Impact on performance was negligible, and we now have an easy knob to turn for horizontal scalability.

The before and after error cliff 2:

The limits of operation

Before replacing a system, it’s worth understanding the cause and effect that led the original to fail.

A property of Redis that’s worth understanding is that it’s

a single-threaded program. This isn’t strictly true

anymore because background threads handle some operations

like object deletion, but it’s practically true in that all

executing operations block on access to a single flow

control point. It’s relatively easy to understand how this

came about – Redis’ guarantee around the atomicity of any

given operation (be it a single command, MULTI, or

EXEC) stems from the fact that it’s only executing one of

the them at a time. Even so, there are some obvious

parallelism opportunities, and notes in the FAQ

suggest that the intention is to start investigating a more

threaded design beyond 5.0.

That single-threaded model was indeed our bottleneck. You could log onto the original node and see a single core pegged at 100% usage.

Intersecting failures

Even operating right at maximum capacity, we found Redis to degrade quite gracefully. The main manifestation was an increased rate of baseline connectivity errors as observed from the nodes talking to Redis – in order to be tolerant of a malfunctioning Redis they were constrained with aggressive connect and read timeouts (~0.1 seconds), and couldn’t establish a connection of execute an operation within that time when dealing with an overstrained host.

Although not optimal, the situation was okay most of the

time. It only became a real problem came in when we were

targeted with huge surges of illegitimate traffic (i.e.,

orders of magnitude over allowed limits) from legitimate

users who could authenticate successfully and run expensive

operations on the underlying database. That’s expensive in

the relative sense – even returning a set of objects from

a list endpoint is far more expensive than denying the

request with a 401 because its authentication wasn’t

valid, or with a 429 because it’s over limit. These

surges are often the result of users building and running

high-concurrency scraping programs.

These traffics spikes would lead to a proportional increase in error rate, and much of that traffic would be allowed through as rate limiters defaulted to allowing requests under error conditions. That would put increased pressure on the backend database, which doesn’t fail as gracefully as Redis when overloaded. It’s prone to seeing partitions becoming almost wholly inoperable and timing out a sizable number of the requests made to them.

Redis Cluster's sharding model

A core design value of Redis is speed, and Redis Cluster is structured so as not to compromise that. Unlike many other distributed models, operations in Redis Cluster aren’t confirming on multiple nodes before reporting a success, and instead look a lot more like a set of independent Redis’ sharing a workload by divvying up the total space of possible work. This sacrifices high availability in favor of keeping operations fast – the additional overhead of running an operation against a Redis Cluster is negligible compared to a standard Redis standalone instance.

The total set of possible keys are divided into 16,384 slots. A key’s slot is calculated with a stable hashing function that all clients know how to do:

HASH_SLOT = CRC16(key) mod 16384

For example, if we wanted to execute GET foo, we’d get

the slot number for foo:

HASH_SLOT = CRC16("foo") mod 16384 = 12182

Each node in a cluster will handle some fraction of those total 16,384 slots, with the exact number depending on the number of nodes. Nodes communicate with each other to coordinate slot distribution, availability, and rebalancing.

Clients use the CLUSTER family of commands to query a

cluster’s state. A common operation is CLUSTER NODES to

get a mapping of slots to nodes, the result of which is

generally cached locally as long as it stays fresh.

127.0.0.1:30002 master - 0 1426238316232 2 connected 5461-10922

127.0.0.1:30003 master - 0 1426238318243 3 connected 10923-16383

127.0.0.1:30001 myself,master - 0 0 1 connected 0-5460

I’ve simplified the output above, but the important parts

are the host addresses in the first column and the numbers

in the last. 5461-10922 means that this node handles the

range of slots starting at 5461 and ending at 10922.

`MOVED` redirection

If a node in a Redis Cluster receives a command for a key

in a slot that it doesn’t handle, it makes no attempt to

forward that command elsewhere. Instead, the client is told

to try again somewhere else. This comes in the form of a

MOVED response with the address of the new target:

GET foo

-MOVED 3999 127.0.0.1:6381

During a cluster rebalancing, slots migrate from one

node to another, and MOVED is an important signal that

servers use to tell a client its local mappings of slots to

nodes are stale.

Every node knows the current slot mapping, and in theory a

node that receives an operation that it can’t handle could

ask the right node for the result and forward it back to

the client, but sending MOVED instead is a deliberate

design choice. It trades of some additional client

implementation complexity for fast and deterministic

performance. As long as a client’s mappings are fresh,

operations are always executed in just one hop. Because

rebalancing is relatively rare, the coordination overhead

amortized over the cluster’s lifetime is negligible.

Besides MOVED, there are a few other cluster-specific

mechanics at work, but I’m going to skip them for brevity.

The full specification is a great resource for a

more thorough look at how Redis Cluster works.

How clients execute requests

Redis clients need a few extra features to support Redis Cluster, with the most important ones being support for the key hashing algorithm and a scheme to maintain slot to node mappings so that they know where to dispatch commands.

Generally, a client will operate like this:

- On startup, connect to a node and get a mapping table

with

CLUSTER NODES. - Execute commands normally, targeting servers according to key slot and slot mapping.

- If

MOVEDis received, return to 1.

A multi-threaded client can be optimized by having it

merely mark the mappings table dirty when receiving

MOVED, and have threads executing commands follow MOVED

responses with new targets while a background thread

refreshes the mappings asynchronously. In practice, even

while rebalancing the likelihood is that most slots won’t

be moving, so this model allows most commands to continue

executing with no overhead.

Localizing multi-key operations with hash tags

It’s common in Redis to run operations that operate on

multiple keys through the use of the EVAL command with a

custom Lua script. This is an especially important feature

for implementing rate limiting, because all the work

dispatched via a single EVAL is guaranteed to be atomic.

This allows us to correctly calculate remaining quotas even

when there are concurrent operations that might conflict.

A distributed model would make this type of multi-key

operation difficult. Because the slot of each key is

calculated via hash, there’d be no guarantee that related

keys would map to the same slot. My keys

user123.first_name and user123.last_name, obviously

meant to belong together, could end up on two completely

different nodes in the cluster. An EVAL that read from

both of them wouldn’t be able to run on a single node

without an expensive remote fetch from another.

Say for example we have an EVAL operation that

concatenates a first and last name to produce a person’s

full name:

# Gets the full name of a user

EVAL "return redis.call('GET', KEYS[1]) .. ' ' .. redis.call('GET', KEYS[2])"

2 "user123.first_name" "user123.last_name"

A sample invocation:

> SET "user123.first_name" William

> SET "user123.last_name" Adama

> EVAL "..." 2 "user123.first_name" "user123.last_name"

"William Adama"

This script wouldn’t run correctly if Redis Cluster didn’t provide a way for it to do so. Luckily it does through the use of hash tags.

The Redis Cluster answer to EVALs that would require

cross-node operations is to disallow them (a choice that

once again optimizes for speed). Instead, it’s the user’s

jobs to ensure that the keys that are part of any

particular EVAL map to the same slot by hinting how a

key’s hash should be calculated with a hash tag. Hash tags

look like curly braces in a key’s name, and they dictate

that only the surrounded part of the key is used for

hashing.

We’d fix our script above by redefining our keys to only

hash their shared user123:

> EVAL "..." 2 "{user123}.first_name" "{user123}.last_name"

And when calculating a slot for one of them:

HASH_SLOT = CRC16("{user123}.first_name") mod 16384

= CRC16("user123") mod 16384

= 13438

{user123}.first_name and {user123}.last_name are now

guaranteed to map to the same slot, and EVAL operations

that contain both of them will be trouble-free. This is

only a basic example, but the same concept maps all the way

up to a complex rate limiter implementation.

Simple and reliable

Transitioning over to Redis Cluster went remarkably smoothly, with the most difficult part being shoring up one of the Redis Cluster clients for production use. Even to this day, good client support is somewhat spotty, which may be an indication that Redis is fast enough that most people using it can get away with a simple standalone instance. Our error rates took a nosedive, and we’re confident that we have ample runway for continued growth.

Philosophically, there’s a lot to like about Redis Cluster’ design – simple, yet powerful. Especially when it comes to distributed systems, many implementations are exceedingly complicated, and that level of complexity can be catastrophic when encountering a tricky edge in production. Redis Cluster is scalable, and yet with few enough moving parts that even a layperson like myself can wrap their head around what it’s doing. Its design doc is comprehensive, but also approachable.

In the months since setting it up, I haven’t touched it again even once, despite the considerable load it’s under every second of the day. This is a rare quality in production systems, and not found even amongst some of my other favorites like Postgres. We need more building blocks like Redis that do what they’re supposed to, then get out of the way.