Hello from a new decade!

It’s already been a great reading day for retrospectives on the last ten years / predictions for the next. Here’s to hoping that everyone had a good break (or at least a few days off), set or didn’t set resolutions, and is refreshed and ready for what comes next.

You’re reading the first 2020 edition of Nanoglyph, a fledgling newsletter on software, sent weekly. Theoretically you signed up for this, and probably did so in the last week or two – but if you’re looking to shore up your mail subscriptions in the new year already, there’s an easy one-click unsubscribe in the footer. If you’re viewing it on the web, as usual you can opt to receive a few more in the future by subscribing here.

I’m playing with the usual format to do a medium dive into an active frontier: web technology in Rust. The language and its ecosystem have seen a lot of change over the last few years and I would have advocated against it in serious projects for its evanescent APIs alone. But there’s good reason to be optimistic about the state of Rust coming into 2020 – critical features and APIs have stabilized, substrate libraries are ready and available, tooling is polished to the point of outshining everything else. The keystones are finally set, ready to bear load.

Many in the web development community will already be familiar with the TechEmpower web framework benchmarks which pit various web frameworks in various languages against each other.

Benchmarks like this draw fire because although results are presented definitely, they can occasionally be misleading. Two languages/frameworks may have similar performance properties, but one of the two has sunk a lot more time into optimizing their benchmark implementation, allowing it to pull disproportionately ahead of its comrade. It tends to be less of an issue in the long run as benchmarks mature and all implementations get more optimized, but it’s a good idea to consider all benchmarks with a skeptic’s critical mind.

That said, even if benchmark games don’t tell us everything, they do tell us something. For example, no matter how heavily one of the Ruby implementations is optimized, it’ll never beat PHP, let alone a fast language like C++, Go, or Java – the inherent performance disparity is too great. Results aren’t perfect, but they give us a rough idea of relative performance.

Round 18 + Fortunes

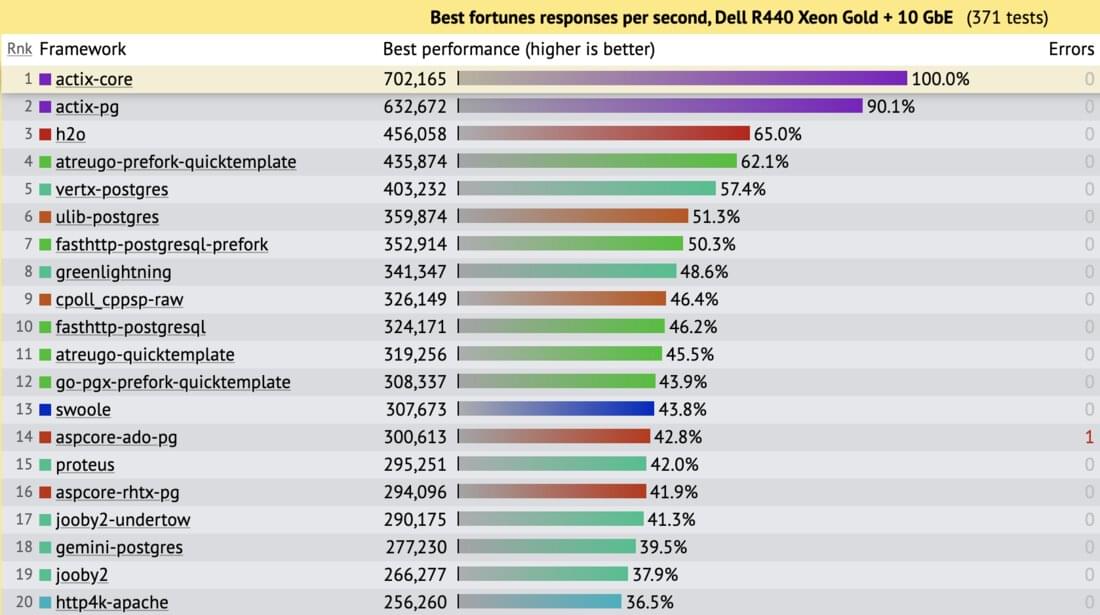

An upset during the latest round (no. 18, run last July) was Actix Web pulling ahead of the rest of the pack by a respectable margin:

Projects in TechEmpower provide implementations for six different “test types” that vary in requirement from sending a simple plaintext response to more complex workloads involving databases. These are the results from the Fortunes test type, which tasks implementations with a simple but realistic workload exercising HTML rendering, DB communication, and unicode handling. Here’s the official description:

In this test, the framework’s ORM is used to fetch all rows from a database table containing an unknown number of Unix fortune cookie messages (the table has 12 rows, but the code cannot have foreknowledge of the table’s size). An additional fortune cookie message is inserted into the list at runtime and then the list is sorted by the message text. Finally, the list is delivered to the client using a server-side HTML template. The message text must be considered untrusted and properly escaped and the UTF-8 fortune messages must be rendered properly.

Fortunes is the most interesting of TechEmpower’s tests because it does more. The trouble with the simpler tests that do something like send a canned JSON response is that they have more than a dozen frameworks that perform almost identically – they’ve all excelled at ensuring that one short piece of the pipeline is well optimized. Fortunes requires a greater range of important real-world functions to all perform well.

Actix Web

Actix Web is a light framework written in Rust. I first wrote about using it for a project a year and a half ago, and am happy to report that unlike some of Rust’s other web frameworks, Actix Web has been consistently well-maintained throughout that entire period and stayed up-to-date with new language features and conventions. Notably, its 2.0 release which integrates Rust’s newly stable standard library futures, shipped this week.

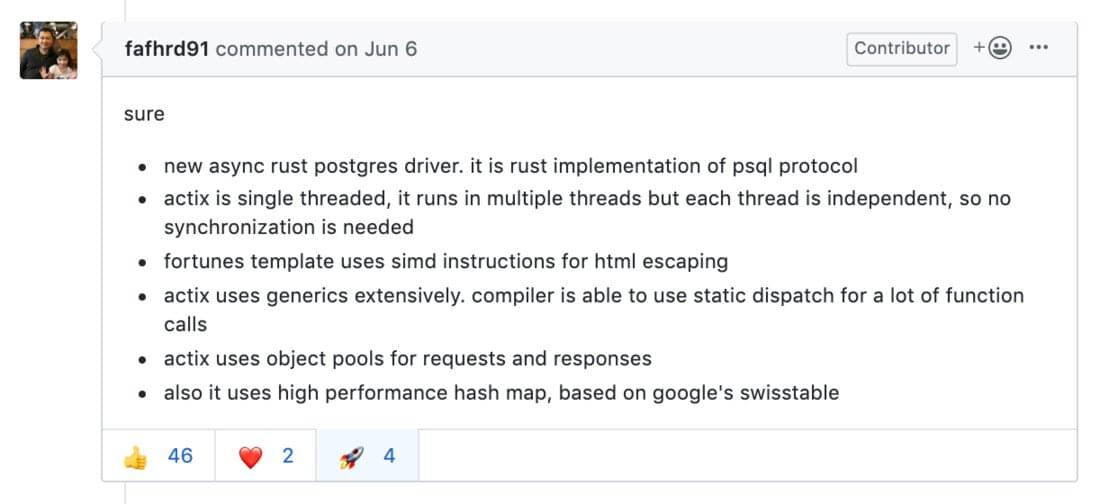

When asked about Actix’s new lead, Nikolay (@fafhrd91), Actix’s creator and stalwart steward, described the improvements that led to it in his typical laconic style:

I found this information fascinating, and the rest of this edition is dedicated to digging into these points in more depth. There are a variety of competing Actix implementations (actix-diesel, actix-pg, etc.) in the benchmark that vary in their makeup and composition – I’ll be looking specifically at actix-core, the current top performer.

Native Postgres drivers

new async rust postgres driver. it is rust implementation of psql protocol

Rust has had a natively-implemented Postgres driver for quite some time, but more recently it also has an asynchronous natively-implemented Postgres driver (tokio-postgres, a new crate but part of the same project). It plays nicely with Rust’s newly stable async-await syntax, standard library Future trait, and tokio 0.2, a new version of tokio with a totally revamped runtime.

Its asynchronous nature allows pauses on I/O to be put to use by having other tasks in the runtime worked during the wait. It supports client pipelining which allows it to be waiting on the responses of many concurrently-issued queries all at once. Better yet, pipelining activates automatically whenever multiple query futures are polled concurrently.

Bottleneck-free concurrency and parallelism

actix is single threaded, it runs in multiple threads but each thread is independent, so no synchronization is needed

To maximize performance, Actix uses a combination of threading for true parallelism and an asynchronous runtime for in-thread concurrency. Starting an Actix web server spins up a number of worker threads (by default equal to the number of logical CPUs on the system) and creates a tokio runtime for async/await handling inside each one.

No state is shared between threads by default, although users can use various Rust primitives to synchronize access to some shared state if they’d like to. In the case of actix-core, each thread spawned get its own local Postgres connection, so no thread waits on any other as it’s serving requests.

struct App {

db: PgConnection,

...

}

fn new_service(&self, _: ()) -> Self::Future {

const DB_URL: &str = "postgres://...";

Box::pin(async move {

let db = PgConnection::connect(DB_URL)

.await;

Ok(App {

db,

...

})

})

}

High octane escape

fortunes template uses simd instructions for html escaping

Some low-level tasks in software are performed so often that they’re worth optimizing aggressively, even if the resulting implementation is fiendishly complex compared to the original.

Recall from the description of Fortunes above that fortune messages must be treated as untrusted, and therefore need to be properly HTML escaped before being HTML rendered. Actix escapes using v_htmlescape, which optimizes HTML escaping through SSE4, a set of Intel SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data) instructions that parallelize operations on data at the CPU level. SSE 4.2 in particular adds STTNI (String and Text New Instructions), a set of operations that perform character searches and comparison on two inputs of 16 bytes at a time. Although designed to help speed up the parsing of XML documents, it turns out they’re also useful for optimizing web-related features.

See sse.rs in the v_escape project to get a feel for how this works. Notably, although the code is unsafe, the entire implementation is still written in Rust – no need to drop down to assembly or C as would be common practice in other languages.

Static dispatch

actix uses generics extensively. compiler is able to use static dispatch for a lot of function calls

Actix uses generics essentially wherever it’s possible to use them, which means that the functions that need to be called as part of an application’s execution are determined precisely during compile time. This is a form of static dispatch, and means that the program has less work to do during runtime. The alternative is dynamic dispatch, where a program uses runtime information to determine where it should route a function call.

For example, an Actix server is built by specifying a ServiceFactory whose job it is to instantiate a Service, each of which is a trait implemented by a user-defined type. All of it uses generics (code below from actix-core):

// Per-thread user-defined "service" structure.

struct App {

db: PgConnection,

...

}

impl actix_service::Service for App {

...

}

//

// ---------------------------------------------

//

// A factory for Actix to use to produce services.

#[derive(Clone)]

struct AppFactory;

impl actix_service::ServiceFactory for AppFactory {

type Service = App;

...

}

//

// ---------------------------------------------

//

// Program entry point specifying typed factory.

fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

Server::build()

.backlog(1024)

.bind("techempower", "0.0.0.0:8080", || {

HttpService::build()

.h1(AppFactory)

.tcp()

})?

.start();

...

}

Recycling requests and responses

actix uses object pools for requests and responses

A peripheral benefit of a language that doesn’t use a garbage collector is that it can provide a hook that gets run immediately and definitively 1 when an object goes out of scope, a feature that most of us haven’t seen since destructors in C++. In Rust, the equivalent is called the Drop trait.

Actix leverages Drop to implement request and response pools. On startup, 128 request and response objects are pre-allocated in per-thread pools. As a request comes in, one of them is checked out, populated, and handed off to user code. When that code finishes with it and the object is going out of scope, Drop kicks in and checks it back into the pool for reuse. New objects are allocated only when pools are exhausted, thereby saving many needless memory allocations and deallocations as a web server handles normal traffic load.

impl Drop for HttpRequest {

fn drop(&mut self) {

if Rc::strong_count(&self.0) == 1 {

let v = &mut self.0.pool.0.borrow_mut();

if v.len() < 128 {

self.extensions_mut().clear();

v.push(self.0.clone());

}

}

}

}

Swiss tables and beyond

also it uses high performance hash map, based on google’s swisstable

This point has become dated in just the six months since Nikolay wrote it. At the time, Actix was using the hashbrown crate, which provided a Rust implementation of Google’s highly performant “SwissTable” hash map. Since then, hashbrown migrated into the standard library to become the default HashMap implementation for all of Rust.

A related development is that Actix now uses fxhash instead of Rust’s built in HashMap in a number of places like routing, mapping HTTP headers, and tracking error handlers. fxhash doesn’t reimplement HashMap completely, but uses an alternate hashing algorithm that’s very fast, even if not cryptographically secure (and therefore not recommended anywhere user-provided data is being used as input). It hashes 8 bytes at a time on a 64-bit platform, compared to the one byte in other algorithms.

Its benchmarks show a very significant edge over other hashing algorithms commonly found in the Rust ecosystem like SipHash (HashMap’s default algorithm), FNV (Fowler-Noll-Vo), and SeaHash, as long as keys are greater or equal to 5 bytes in length.

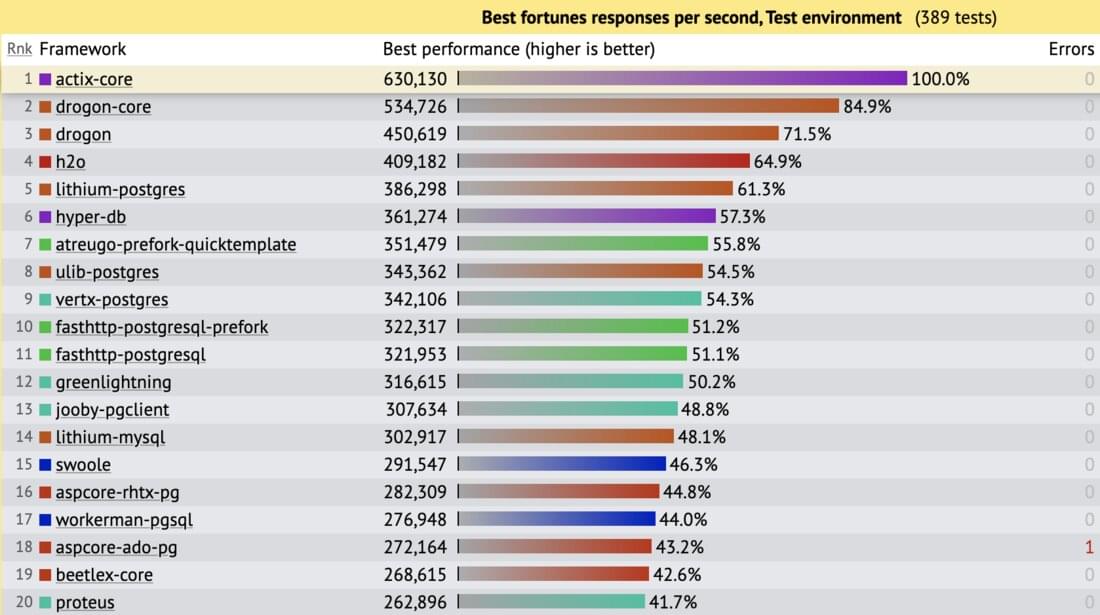

Round 18 is now half a year out of date, so you might reasonably ask, how is Actix stacking up today? The question’s especially relevant because the previous set of results were all prior to the project’s 2.0 release, and the road to 2.0 involved significant structural changes. Luckily, TechEmpower has regular interim runs going between official rounds, and one finished up just this morning (see run@aeb5fd9d).

Results are similar to round 18, with actix-core showing a substantial lead over anything else, and the same relative lead compared to most implementations common to both rounds. The most notable change is that there’s a new contender for the top of the charts in the form of Drogon, a C++ framework with its own asynchronous design. Actix is still outpacing it by a healthy margin, but Drogon in turn is leading the next framework by a wide margin of its own.

I’m challenging myself to write 30 editions of Nanoglyph in 2020. Its a time sink, but worth it. Similar to Feynman’s learning technique, having to dig into a subject to explain it to someone else is one of the best ways to solidify understanding. The weekly cadence is good exercise in getting words on paper quickly. I have a tendency to write at a snail’s pace as the choice of every word is agonized over with excruciating attention – a time-guzzling anti-habit that I’d love to knock over in the new year.

The newsletter’s format continues to be open. A goal for the project is that quantity shouldn’t negate a solid baseline of quality. I’m keeping an eye on that, but it’s easy to lose objectivity on something you’ve been staring at for this long, so I could use some feedback on what content you’ve found useful so far, or suggestions on what you’d like to see (or don’t want to see). If you have any ideas along those lines and can spare a minute – hit the “Reply” button and send them my way.

Happy new year! Until next week.

1 A C++ destructor or Rust Drop implementation differs from something like a C# finalizer in that while the runtime does guarantee that the latter will eventually be called, it gives no guarantee as to when.